In the Atyah Lane days, I vaguely remember going into bustling downtown Rangoon to have family photo portraits done. Or was it during the time that we lived in the village house? The village house, for lack of a better term, was another sunny house in that it was in the open, at the end of a friendly road, and part of an extended family village. The house was on stilts, as are most Burmese houses, and the walls were of woven bamboo. This type of building is well suited to the hot tropical climate. The woven walls allow for air to circulate and maintain a cool interior. The floors were smooth wooden planks. The bathroom was a refined outhouse and the shower water was taken directly from barrel drums containing rain water. One poured the water from a ladle and the water would drain away from the cracks in the wooden floor planks. Laundry was done by the women relatives – aunts and servants, mothers and grandmothers – who would soap and rinse the clothes, wringing them out and then beat them on rocks. It was all such a fascinating play in water and I received a deep blessing in the ways of water from these early experiences.

Public bathing was quite acceptable in places where a drum would hold rain water, on a cement or stone platform. I sometimes felt squeamish around those places because they would be slippery with slimy mold. I would recoil from touching those surfaces. Women would deftly hold a corner of their longyis, or sarongs, unbound, in their teeth and douse themselves with water, wringing their long black hair, which would later be conditioned with coconut oil. To deflect the heat of the day, women and girls smear a paste called thanaka, made from the bark of a tree believed to have medicinal cooling properties, onto their cheeks.

The village house was surrounded by other houses on one side. A road lined with coconut palm trees led to the house. There was also a Buddhist altar about 6 feet high on a pole in front of the house, but near the road, where my aunts and grandmother made offerings. It would often be lit at dusk, like many other altars throughout the village and throughout Burma. There was a Lilliputian stream on the side where the other houses were. I loved to play by the stream and watch the glittering water as it made little eddies and burbling sounds. Most delightful of all were the water chestnut plants that grew along its banks. I would squat and eat the crispy, delicious, fresh, raw water chestnuts, picking away their brown skins, all the while enjoying the green canopy overhead and the benevolent sun lighting up this magical green and watery world. It was my own private Eden.

Behind the house there was a chalk factory, which seemed abandoned, yet mysteriously workable. And behind the chalk factory was the jungle which dipped away, wild and green. My mother often warned us not to play in the chalk factory and especially not in the jungle. Still, being kids, those areas called to us to come and play. My brother and I stood at the edge of the jungle one day and saw a bright green and poisonous snake, perhaps eight feet long, coiled, around the branch of a tree. My brother couldn’t resist approaching and throwing stones at the snake, which became perturbed but not overly eager to leave its perch. I watched the snake’s reaction and became increasingly frightened that it might slither off the branch and chase us, so I ran back towards the house.

We had a gardener in the village house, as we did in the Atyah Lane house, who tended to all the plants around the house. My favorite of all the plants was a small tangerine tree in the front of the house. It couldn’t have been more than 7 feet tall but it was large enough to house a little girl, me, within its branches. I would roost in that tree and eat the fruit and survey the world, protected by branches of citrus leaves and bright orange fruit.

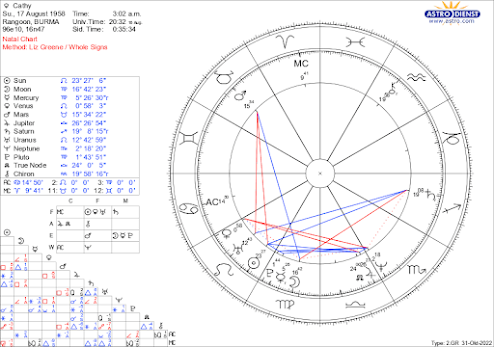

My mother tells me that I used to swear “like a fishmonger” in those days. I was usually quite placid, but when angry, became “mad as a bull” (quite like my Mars in Taurus square Uranus in Leo). My mother had tried to get me to stop swearing but nothing worked. I enjoyed nothing better than to let out a stream of expletives at the top of my lungs for all to hear and if it offended anyone, too bad, it was fun! One day, after yet another round of my public display of expletives, my mother, in desperation, took me out to the chalk factory, pushed my head down over a drain, and with the cold water running where the chalk mixture would have flowed, shoved a white bar of soap into my mouth. With brusque movements, she washed my mouth vigorously with the awful tasting soap. I allowed her to continue until she was satisfied with the duration and severity of the punishment. Her anger spent, she finally stopped. Unruffled by the cleansing, I looked up at her fixedly and exclaimed, “oh, that was good!” I continued to enjoy swearing and swore every chance I got.

I remember Christmas in this house, and a Buddhist festival, and a New Year celebration. The Christmas tree had big colored lights and we sang “Oh Christmas Tree”. My maternal grandmother, Louisa Ling, once set up a cauldron filled with hot fat over an open fire and made doughnuts, the most delicious doughnuts I’ve ever had, and I think it was my birthday! My mother made a traditional festive Burmese sweet drink that contains, among other things, tiny blocks of cold gelatinous inky sea weed. There were strings of colorful lanterns in the front of the house for the celebration. The night air was gentle and sensuous in a way that one can only feel in the tropics, I'm sure of it. The celebration may also have been New Year’s or Buddhist October festival.

It was in the village house that my nanny created meticulous styles with my hair. One that I liked in particular featured a pony tail on the very top of my head. The hair was allowed to fall open, fountain like and folded under, into a mushroom shaped bun (in physics, a torus). The bun was then decorated with tiny white paper flowers resembling mimosa. My nanny would do anything that I asked. She once made me a fried egg for a snack when I complained of being hungry. After eating the egg, I told her I was still hungry, so she made me another egg. And so it continued till I had consumed 5 or 6 eggs. My mother was very upset when she heard about this later from the nanny and she encouraged her to not give in to my demands. I think she was upset not only by the number of eggs I had eaten but also my apparent joy in bossing the nanny.

I would spend my days playing under the house which, being on stilts, had a 3 or 4 foot crawl space. It was dry beneath the house, useful for play during monsoon downpours, a perfect home beneath a home in which to play house. I would pretend to cook in an old tin can filled with water and spend hours preparing the pretend soup. My favorite activity was cutting with a little bamboo knife that my father made for me – it was nothing more than a large sliver of bamboo sharpened along one side, but harmless. For my slicing pleasure I would collect banana peels and leaves of all kinds. I loved the way the “ingredients” felt in my hands and under the blade of the knife. Thick juicy leaves were a real treat to cut. I would inspect the surface of leaves and look within, seeing structures and imagine unseen green mysteries. The banana peels were versatile in that they could be sliced and also scraped for their fibrous interior right down to the yellow portion of the peel and then sliced. I would drop the leaves and banana peels into the tin can pot which I pretended was boiling and I would stir, stir, stir the soup until it was ready to serve. I never did get to the serving part of the meal. Cooking it was enough. My love of cooking started then as an innate urge to play with raw ingredients. Fire was an important element that I missed but resigned myself to doing without. I knew I was a child and could not be allowed to play with fire. But oh how I missed it! I consoled myself with quiet moments by my little secret stream, away from the prying eyes of elders, where I could squat and sample the tasty water chestnuts. I also picked and ate little red flowers which grew in the sunny front yard – I see them in the U.S. – in the begonia family, I think – and I never got sick. They had a delightful tartness that I found hard to resist so I would pick and eat as I wished. Somehow I knew they were safe to eat. No one ever stopped me or even noticed that I was eating the ornamental flowers. After a while the other children in the village compound began to join me for this floral banquet. None of us got sick.

The women servants and some of my aunts and cousins would begin the day by bathing and meditating and making offerings to Buddha and the nats, animistic spirits who lived in the trees and throughout the natural world. Then they would walk to market in Rangoon center along a dusty road, already hot in the early morning in most seasons. In the cool season, October through February, it was always so pleasant to greet the gentle colors of the quiet day and walk hand in hand with one of the servants, usually my nanny, or with an aunt or my grandmother. My mother did not do these chores on a regular basis. She had servants and the help of women on my father’s side of the family. In the green peace of the morning my paternal grandmother, Daw Shwe (which translates to “Golden Lady”), who was one hundred percent Burmese, would take me gently by the hand to a dewy field. There we would walk through the frangrant grass and pick the tenderest little button mushrooms. How delicious they tasted, magical mushrooms, served later that day at lunch, simply stirfried. I can still taste the mystery of their flavor, part nocturnal nectar, part sun and dew! I can still feel Daw Shwe's presence as I write, alive and vibrant, so loving and wise, my hand in hers.

Like all markets, Rangoon’s was bustling. Whoever I tagged along with would inevitably end up haggling over a purchase, maybe a chicken or household item. The market sold meats, fruits and vegetables, housewares and crafts brought from the hill villages around Rangoon. The crowd was diverse as well – farmers, craftsmen, artisans from various hill tribes dressed in their traditional tribal garb, each distinct in the types of fabrics and designs. There were Burmans too from the Irrawaddy delta, of which Rangoon is the epicenter.

As the morning wore on, the market’s stench increased due to the lack of refrigeration. Big fat flies would buzz around the meats being chopped on huge wooden slabs. The purveyors of pork would sit crossed legged right on their raised chopping blocks and hack off pieces of meat with giant chinese cleavers. Burmese laypeople are not usually strict vegetarians but due to the scarcity of meat, especially beef, they tend not to each much meat but to stretch it in curries. They cook with meat as much for the flavor it lends to the curry gravy as for the protein in the meat itself.

The women would return from market by 9 AM and begin cooking for the entire day. Light soups were often a favorite served with richer curries, as sides, for the main dish of rice. The soups were flavored with dried shrimp and garlic and usually some type of gourd. Sometimes, I would gather leaves from a certain tree or pick water spinach by the stream to add to the soup. These plants were esteemed not just for their flavor but for what was considered their cleansing, tonic properties.

One of my aunts had a friend who owned a shop. It was probably not much more than a makeshift shelter. There were numerous colorful clothes hanging, serving as doors. The friend asked me if I was hungry, took me into the back of the shop and made me a plate of rice and dahl with fried whole chilis on the side. The chilis were hot and smoky and burned my lips but I was undaunted, finishing off the whole thing. Simple as it was, it remains one of the most memorable meals of my life, probably certainly the first one that I remember clearly.